George Hood

It is paradoxical that so much emphasis has been placed on ‘global’ food security by leading institutions such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation and the World Trade Organisation, and yet the chasm separating the damning realities of malnutrition and the neoliberal vision of food production has never been more visible. This disconnect between policy and its effects is most obvious in the Horn of Africa, where undernourishment has been prevalent amongst a third of the population since the start of the millennium. At the same time, agriculture is seen as the dominant economic sector in the Horn, and is placed at the centre of development debates for this region.

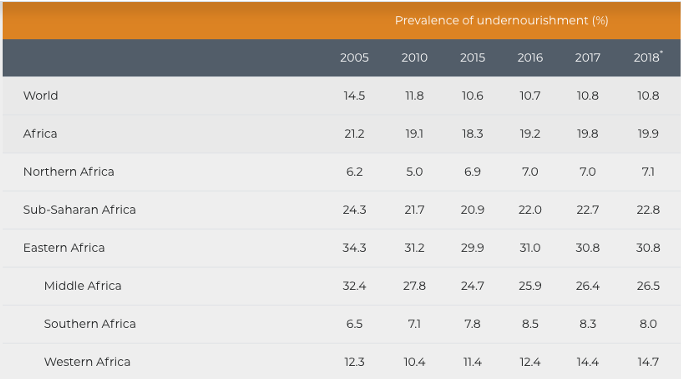

Undernourishment as a percentage of the overall population is consistently higher in East Africa than other parts of the continent, and three times higher than the global average.

Statistics provided by the FAO.

In the midst of the neoliberal era, East African governments have been inclined to change land tenure laws and sell off agricultural plots to agribusiness companies. Cash crops and raw agricultural goods under the international division of production (and labour) are grown for export, either for sale in foreign markets or for more complex manufacturing processes elsewhere. Under this regime, agricultural output has been very high, but does this reflect a sustainable process?

Women, youth and the environment are positioned to see the worst impacts of this trend. By unpicking the data, the rise of agribusiness dominance has coincided with a decline in small-scale, agro-pastoralist farming systems. These farming systems often rely on ‘domestic’ inputs from women and youth, as well as from the ‘land’.

Kate Raworth, a professor of economics at Oxford, has pointed to how most economic systems are conceptualised as being closed and anthropocentric. They do not consider environmental and domestic inputs, as well as environmental outputs – damage! She has developed her theory of ‘doughnut economics’ as a way of pitting human needs against planetary boundaries. In this context, neoliberal agriculture is the antithesis of sustainable ‘doughnut economics’. Monoculture for export entails an intensive process in every sense of the word besides labour: chemicals, technology, and capital. All the while the environment is neglected on the basis that caring for it is irrelevant to the short-term, low-risk, high-yield returns for agribusiness shareholders.

A simplified version of Kate Raworth’s theory – ‘doughnut economics’. The green ring represents the balance of ensuring livelihoods and minimising ecological damage.

Building on previous notions of ‘food sovereignty’ and ‘agroecology’, Kate Raworth’s theory shows that the inputs of the environment and women don’t just have instrumental use; they are essential parts of agricultural production and need to be protected under radically different food regimes that aren’t only interested in aggregate output and return-on-investment.

In PENHA’s 2020-25 five-year strategy, the organisation is trying to put community-based organisations at the centre of decision-making. Information sharing is seen as dialectical at PENHA; agro-pastoralists pass their strategies onto the organisation and academics/policymakers throughout the Horn, and this information contributes to papers that form policy and development projects which will ensure the sustainability of small-scale farming. PENHA works with women and youth in particular, as it recognises their centrality to agro-pastoralism. The organisation also works to empower youth by partnering up with Universities in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

A meeting about Prosopis with Sudanese agro-pastoralists. PENHA works to put women at the heart of agricultural development as the majority actors in the community-based agricultural process.

Raworth’s ‘doughnut economics’ is also useful as it groups economic actors into two categories: those who care for exceeding ‘planetary boundaries’ and those who don’t. Governments are becoming more socially responsible for their actions in the Horn, brought about by waves of protests and democratisation. In light of this, they now join the group of ‘those who do’, as environmental damage will only have harsh electoral and economic consequences for them. Joining them are small-farming communities, civil society and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs). On the other hand, we have ‘those who don’t’ – corporate power that defends its interests through monopoly and lobbying. This coincides with PENHA’s strategy of building regional cooperation across the Horn, where it seeks to defend agro-pastoralism from the clutches of agribusiness.

Whilst PENHA is currently trying to ensure secure livelihoods for agro-pastoralists, its activities and ideology shows strengths that transcend the myopia of our current food production regime under neoliberalism. The ideas of ‘food sovereignty’ and ‘doughnut economics’ are symbiotic with PENHA’s aspirations: to ensure sustainable agriculture-led development across the Horn of Africa.

Food sovereignty can only be achieved in a policy space where agro-pastoralists – those with the greatest understanding of the relationship between people and land – have the autonomy to lead by example.

Short bio

Having recently graduated with BSc in Development Studies course at SOAS, I am managing a Coffee Company and Social Enterprise. The Colombian Coffee Company is based out of Borough Market and supports independent farming communities impacted by the conflict in Colombian by offering a fair price for coffee, disconnected from the international market. I am also using my experience at PENHA to help the company start a charity, to establish truly direct and ‘fair’ trade with small-scale coffee producers.